by NICHOLAS FISK and DANIEL OWENS

We have got so used to the gap between the funded and true costs of research that it’s almost endemic. Yet the Accord’s call for bold transformative solutions to sectoral woes must now place this one front and centre of its to-do list. Especially as the gap is yawning, with the fixed pie of the Research Block Grant failing to account for the extra Medical Research Future Fund and commercialisation scheme mouths it must now feed.

How big is the gap?

It’s difficult to be exact. The best current estimate comes from 2020 ABS data on Australian universities comparing total R&D spend to external R&D income. This shows that for every $1 of external R&D revenue, institutions spend an additional $1.14 from own source income. Other estimates vary, the 2018 Laming Inquiry noted shortfalls of between $0.47 to $1.71. In the Accord submissions, the G08 plumped for a rounded $1 albeit less than earlier estimates, while Universities Australia referenced a 2008/9 exercise ranging from $0.60-$1.37, with a mean of $0.99 in research intensive institutions.

Although it’s the indirect cost gap between grant dollars and full economic costing that gets the headlines, there is also a direct costs problem, as the amount requested in applications rarely gets awarded by major funders. Little over 70 per cent was paid out for successful Australian Research Council Discovery Projects in 2022, while National Health and Medical Research Council standard salary awards are often around half what are required under enterprise agreements.

Universities must also stump-up salary gaps for most external fellowship schemes. And then for mega-awards such as centres of excellence or cooperative research centres, universities are increasingly required to co-invest as part of actual or implied grant requirements. At UNSW, this leverage impost alone cost us $32M last year, meaning that we write-off RBG before we even see it.

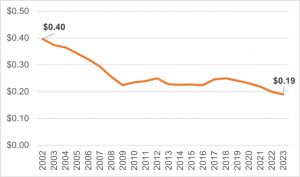

The government instrument to support universities in meeting the underpinning costs of research is the Research Support Program component of RBG. RSP is grossly underfunded, making up only 14 per cent[1] of the indirect costs per dollar it is intended to cover, and the situation is worsening. This is because newer federal funding opportunities like the Medical Research Future Fund ($650M pa) and the University Research Commercialisation Action Plan ($2.2bn) have been introduced with no proportionate or indeed any supra-CPI increase in RSP. The impact of this has seen the average RSP returncontinue a long run downward trend, from a high of 40 cents two decades back to less than half that now in 2023[2]. It is also reflected in the widening gap between increases in HERDC income and overall RBG (9.7% vs 1.2% over the three years to 2021). Someone is not pulling their weight.

RSP return (or comparable precursor) per $ HERDC 2002-2023

What are the fixes?

The simplest approach is the big bang one of upping RSP. Advantages are ease of introduction, as the pre-existing system is already in place and not tied to individual grants, affording universities flexibility in how to best support their research.

Importantly it covers all categories of research income, in line with the need to boost end-user translation and commercialisation, as well as the re-embracing of blue skies research in the national interest. The chief hurdle is affordability: extrapolating from the ABS figure of $1.14 suggests that injection of a hefty $5.8bn would have been needed nationally this year, nearly six times current RSP! And if this did come to pass, it would be crucial to avoid opening the flood gates for funders to encroach on the extra RBG pot to demand increased leverage to offset their own awards.

A more cautious approach is for central funders to meet research support costs. This at least begins with the research councils, adopting an evidence-based full economic costing approach to awards. Put simply the real costs (direct and indirect) need to be shown. These are precisely and transparently determined for inclusion in grant applications, with a large proportion then funded, as happens in the UK, Finland, and the US.

This would certainly be cheaper, albeit modelling suggests still needing an empiric $1.9 to 2.0B to meet the current FEC gap, and more like $2.4 to 2.5bn p.a. for new ARC, NHMRC and MRFF awards over and above RSP. It begins at the top with a Category 1 quality filter, but why not then broaden to encompass all government funded research, including from the jurisdictions?

One disadvantage with the central approach is that it does not extend to philanthropic or commercial funding, driving a shift away from these towards FEC payers. Philanthropy of course is to be welcomed, though showering millions of government support on say a Picasso windfall sounds questionable. Industry could pay its share as they do with CSIRO, in contrast to Australian universities which typically grossly undercharge indirect costs; altering this though might fly in the face of the industry engagement agenda. Another disadvantage is the vulnerability of research councils to budget freezes and fixed pie approaches – in particular grant success rates must not plummet to meet FEC. Adopting this approach without a budget uplift would be disastrous; modelling based on the ABS gap figure warns that awards would halve with success rates well below 10% for ARC and NHMRC schemes, a

| No indirect cost support – current | FEC Approach | |||||

| Scheme | Avg. Amount | Awarded | Success rate | Avg. Amount | Awarded | Success rate |

| ARC Discovery Project | $463,168 | 478 | 18.5% | $977,284 | 227 | 8.8% |

| ARC DECRA | $428,954 | 200 | 15.0% | $905,094 | 95 | 7.1% |

| ARC Future Fellowship | $942,498 | 100 | 15.9% | $1,988,672 | 47 | 7.6% |

| NHMRC Ideas Grants | $1,038,437 | 232 | 11.0% | $2,191,102 | 110 | 5.2% |

| NHMRC Investigator Grants | $1,669,502 | 225 | 15.9% | $3,522,649 | 107 | 7.5% |

Other options include a leverage scheme where the Commonwealth incentivises universities by paying an additional fixed percentage of their R&D investment, or incentivises industry through a premium tax credit for collaborative research with publicly funded research organisations. All these approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The time is nigh

The budget has kicked the research funding can down the road to the Accord. There is fierce agreement that the Accord presents a pivotal and timely opportunity to reset research funding towards a much-needed full cost basis. The challenge is in how to achieve this, between a blanket block grant type system versus grant associated on-costing, the latter needing less than half the national uplift but covering only the third of HERDC that is NHMRC/ARC/MRFF. Yes the full fix cost is eye-watering at $1.9-5.8bn annually, but then government investment in R&D has fallen to an all time low of <5%. And surely the $3.2bn of that in R&D tax offsets is ripe for scrutiny.

This growing gap between research costs and income is hardly a new problem but one that can no longer be left on the backburner. We’ve been minding this gap for too long.

[1] If we consider the total cost of research as $1.14 + $0.19=$1.33, the RSP component is 0.19/1.33= 14.3%.

[2] The current average of 0.19 reflects 0.22 for Cat 1 and 0.16 for Cat 2-4

Nicholas Fisk is DVC (Research and Enterprise) and Daniel Owens is Executive Director (Research & Enterprise) at UNSW Sydney