by MARNIE HUGHES-WARRINGTON and ANDREW KLENKE

The daily chorus of upgrades and patches starts from the devices on and all round me, rippling like the waves of a social spider web. Continuous releases are celebrated as a feature of our digital age, but we have a deep history of tinkering that bursts the bounds of the linear diagrams and numbering systems for innovation, translation and commercialisation that are repeatedly made.

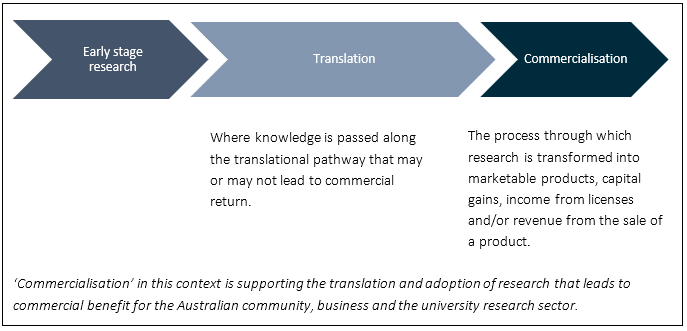

Two linear timelines have sat side by side on my desk in the past week. The first, from the Australian Government’s University Research Commercialisation Consultation paper, depicts the innovation pipeline as three interlocking, sequential arrows.

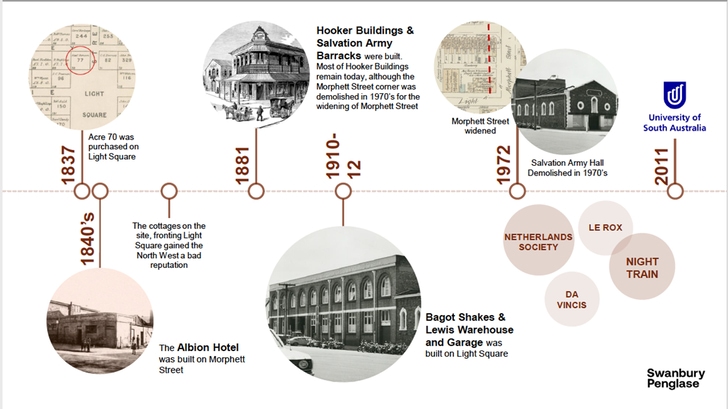

The second provides the first site history for the University of South Australia’s Enterprise Hub.

The urge to compare them is overwhelming given South Australia’s status as Australia’s first settler society testlab.

Settled through a commercial lens, South Australia captures in microcosm the continuous buzzing, twitching, tinkering history of social, economic and technological change.

The UniSA Enterprise HubTM site has hosted a pub, a “monster brothel,” an engineering yard and Salvation Army Hall, produce, crash repair and truck distribution stores, a hide and skin warehouse and export warehouse, Netherlands Club, nightclub and theatre restaurant.

It is striking how many of these activities were start-ups, and how many were co-present at any one time. It was a mixed-use site with varying levels of innovation and social and economic return.

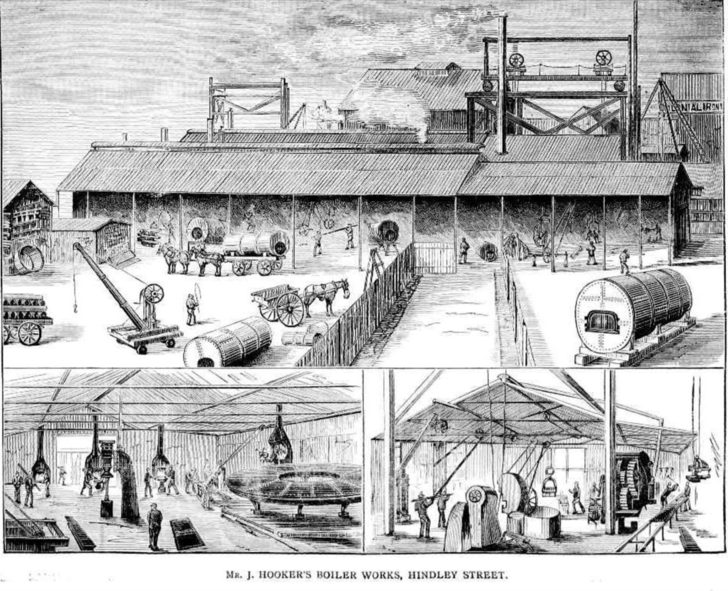

James Hooker’s engineering works of 1881, for example, could have been a prototype for an industry 4.0 testlab. Cutting, curving and riveting machines with magical names such as “wonderful” and “Samson” were used to test and to turn out transformative approaches to the manufacture of civil structures such as bridges.

The testlab sat cheek by jowl with a row of houses in which Thomas Boddington—a man described by the Adelaide Licensing Bench in 1879 as being of “bad fame and character”—had a “beneficial” interest in keeping a brothel. Commercial structures for brothels, as Gerder Lerner has noted, can be dated back to at least the Code of Hammurabi (1755–50 BCE). They too evolved, with regulation shaping and being shaped by different forms of organisation and payment systems.

Hooker won out over Boddington in the end and constructed a temperance hall and meeting place for the Salvation Army. This provides something of a moral to the story, but it is also a commercial tale. The important thing to remember is that innovation is a mixed-use system—a testlab of policy, financial settings and prototyping and producing entities, if you like, and not all of them should be thought of as start-ups.

This brings me to the Government’s depiction of the innovation pipeline. It is all too tempting to read diagrams like this as being about discrete start-ups which aggregate up into a homogenous system, rather than macro, mixed systems.

Start-ups get runway in the testlabs that nurture them. These testlabs are mixed in nature by virtue of the bricolage of funding and support arrangements that must be stitched together with considerable skill by university staff working in translation and commercialisation.

They are also mixed, however, because they host combinations of start-ups, scale-ups, and mature businesses. In these systems, IP is licenced and sold to other entities, as well as disclosed and left to lapse. In these systems, start-ups might be held in incubation to avoid IP dilution. In these systems, organisations may collaborate through a combination of background, downstream, foreground and side-ground IP. In these systems, there is no separation of sectors or of STEM from HASS, or research from education. And in these systems, entities may compete and jostle to push one another out, like Hooker over Boddington.

Mixed systems are often ironed out of the picture when innovation is presented in pipeline form. I don’t buy that history happens in straight lines, and I don’t think we should buy innovation happening in that way either. If we want translation and commercialisation to grow, we need to spend more time thinking about what makes mixed systems work, and to support them. It is strange to focus on translation and commercialisation funding without addressing shortfalls in research funding, for example, and to not think about social as well as economic innovations. We need to think testlabs, not just pipelines, and support them with consistent funding and policy arrangements.

***

Marnie Hughes-Warrington is DVCRE at the University of South Australia

Andrew Klenke is Director, Swanbury Penglase Associates, the appointed Principal Architects for the UniSA Enterprise HubTM.