by MARNIE HUGHES-WARRINGTON, PAT BUCKLEY, INGER MEWBURN &

the ANU PostAC UNIVERSITY TEAM

It wasn’t a strong beginning. As startups go, you probably wouldn’t have rated it a chance. Just over 100 years ago, the modern doctorate was created as a destination degree for the worthy and the solid. Since then, it has remained the edgy member of the global degree suite, with some folks swearing by its intoxicating powers, and others wondering whether it is worth the effort.

Well, as we know, some startups flounder and fall over quickly, and others morph and hit their stride after a slow start. The doctorate is just starting to hit its stride, and it is important to continue to nudge it in the direction of success. That success flows—like any good start up—from knowing who it is for, and adaptation.

If you are starting to form knitted brows, it is possibly because you think that the doctorate serves one purpose: to educate future academics. But if you reframe your reckoning and acknowledge the broader demand for PhD graduates across business, not for profit, government and academic destinations, then the prospects for the degree look different.

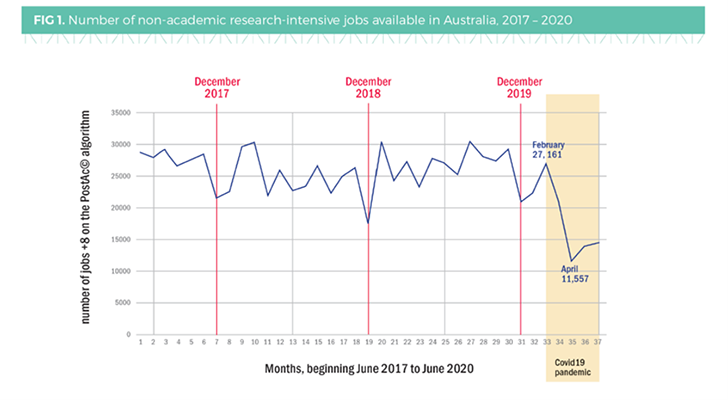

The University of South Australia asked the PostAc team at ANU to analyse over 3 million job ads posted across Australia and within South Australia between 2017 and 2020. In 2017 there were 12 potential jobs for every research degree graduate. In the first quarter of 2020—as you would expect—the job market plunged, but it started to regain ground and hit around 2 potential jobs for every research degree graduate by mid-year.

Backing research capability really matters for our economy, and for broader society, particularly at this time. Part of that backing is understanding the enterprising nature of the PhD, and its market, talking about it slightly differently, and nudging its training requirements.

You have to start by acknowledging that you likely won’t see “has PhD” in the essential criteria for most jobs. Organisations do want research-degree graduates on account of the capabilities they develop through innovation in disciplinary or interdisciplinary knowledge. Pause for a moment and consider what would be on your capabilities wish list for PhD graduates. Then ask yourself whether they coincide with this 3-million job employer top 20 wish list from the UniSA/PostAc report:

| 1. Building relationships | 2. Communication skills |

| 3. Planning | 4. Teamwork and collaboration |

| 5. Project management | 6. Stakeholder management |

| 7. Problem solving | 8. Business acumen |

| 9. Budgeting | 10. Organisation and time management skills |

| 11. Creativity | 12. Detail oriented |

| 13. Leadership | 14. Change management |

| 15. Mentoring | 16. Business development |

| 17. Decision making | 18. Risk management |

| 19. Customer service | 20. Data analysis |

Consider, in turn, how well this list lines up in intent or in language with the Australian Qualifications Framework Level 10 Descriptors. Knowledge looms large in the AQF descriptors, as do autonomy and dissemination to other people. You need to know things, to think for yourself and to be able to explain things to other people. Employers—including university employers—might rightly want to see other capabilities emphasised, such as the need to forge and sustain collaborations; to mentor other people, to work through change with creative capabilities; to understand how to identify and strategise with risks; and to demonstrate computational thinking. These are also the right skills for founders of startups, too.

We should not assume that any one cluster of disciplines delivers these capabilities in spades. Take a look at the compound growth or loss of opportunities for research degree graduates from 2017–20.

| ANZSIC | First half 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | Average – normal | % jobs first half 2020 |

| State Government Administration | 245 | 731 | 475 | 224 | 477 | 103% |

| Hospitals (Except Psychiatric Hospitals) | 161 | 411 | 259 | 224 | 298 | 108% |

| Computer System Design and Related Services | 94 | 246 | 139 | 150 | 178 | 105% |

| Engineering Design and Engineering Consulting Services | 70 | 227 | 244 | 248 | 240 | 58% |

| Other Transport Equipment Manufacturing n.e.c. | 52 | 206 | 17 | 59 | 94 | 111% |

| Banking | 75 | 180 | 167 | 158 | 168 | 89% |

| Accounting Services | 39 | 125 | 116 | 181 | 141 | 55% |

| Central Government Administration | 23 | 117 | 89 | 87 | 98 | 47% |

| Scientific Research Services | 11 | 115 | 159 | 141 | 138 | 16% |

| Local Government Administration | 15 | 110 | 64 | 113 | 96 | 31% |

| Aircraft Manufacturing and Repair Services | 14 | 80 | 33 | 13 | 42 | 67% |

| Water Supply | 1 | 79 | 55 | 83 | 72 | 3% |

| Oil and Gas Extraction | 16 | 75 | 22 | 13 | 37 | 87% |

| Other Social Assistance Services | 71 | 60 | 31 | 54 | 48 | 294% |

| General Insurance | 15 | 53 | 46 | 36 | 45 | 67% |

| Shipbuilding and Repair Services | 10 | 52 | 96 | 118 | 89 | 23% |

| Other Machinery and Equipment Repair and Maintenance | 5 | 52 | 18 | 33 | 34 | 29% |

| Investigation and Security Services | 26 | 44 | 21 | 15 | 27 | 195% |

| Supermarket and Grocery Stores | 22 | 42 | 13 | 28 | 28 | 159% |

| Other Telecommunications Network Operation | 15 | 37 | 35 | 26 | 33 | 92% |

| Public Administration | 14 | 37 | 20 | 21 | 26 | 108% |

| Credit Union Operation | 11 | 33 | 6 | 1 | 13 | 165% |

| Management Advice and Related Consulting Services | 47 | 31 | 14 | 29 | 25 | 381% |

| Mining | 5 | 30 | 32 | 27 | 30 | 34% |

| Other Health Care Services n.e.c. | 5 | 28 | 15 | 22 | 22 | 46% |

| Iron Ore Mining | 3 | 27 | 36 | 94 | 52 | 11% |

| Gas Supply | 0 | 26 | 9 | 4 | 13 | 0% |

| Defence | 11 | 25 | 78 | 79 | 61 | 36% |

| Depository Financial Intermediation | 6 | 25 | 8 | 28 | 20 | 59% |

| Electricity Distribution | 4 | 24 | 22 | 14 | 20 | 40% |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 25 | 23 | 28 | 24 | 25 | 200% |

| Other Heavy and Civil Engineering Construction | 16 | 21 | 22 | 72 | 38 | 83% |

| Other Agriculture and Fishing Support Services | 14 | 21 | 17 | 21 | 20 | 142% |

| Pharmaceutical, Cosmetic and Toiletry Goods Retailing | 2 | 19 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 29% |

| Electricity Supply | 6 | 17 | 31 | 21 | 23 | 52% |

| Paper Bag Manufacturing | 3 | 17 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 64% |

| Education and Training | 5 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 94% |

| Special School Education | 0 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 10 | 0% |

| Educational Support Services | 1 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 29% |

| Legal Services | 5 | 12 | 22 | 23 | 19 | 53% |

| Pharmaceutical and Toiletry Goods Wholesaling | 4 | 12 | 21 | 12 | 15 | 53% |

| General Practice Medical Services | 2 | 11 | 18 | 26 | 18 | 22% |

| Wine and Other Alcoholic Beverage Manufacturing | 4 | 11 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 57% |

| Air and Space Transport | 2 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 50% |

| Insurance and Superannuation Funds | 2 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 52% |

| Other Public Order and Safety Services | 6 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 171% |

| Cement and Lime Manufacturing | 0 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 0% |

| Secondary Education | 1 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 32% |

| Newspaper Publishing | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0% |

Consider, in turn, how well this list lines up in intent or in language with the Australian Qualifications Framework Level 10 Descriptors. Knowledge looms large in the AQF descriptors, as do autonomy and dissemination to other people. You need to know things, to think for yourself and to be able to explain things to other people. Employers—including university employers—might rightly want to see other capabilities emphasised, such as the need to forge and sustain collaborations; to mentor other people, to work through change with creative capabilities; to understand how to identify and strategise with risks; and to demonstrate computational thinking. These are also the right skills for founders of startups, too.

We should not assume that any one cluster of disciplines delivers these capabilities in spades. Take a look at the compound growth or loss of opportunities for research degree graduates from 2017–20 (scroll up).

Australia’s traditional business strengths in finance, services and energy shine through. As argued in Marnie’s previous UniSA blog, these old-new industries are driving innovations in areas such as cybersecurity, digital supply-chain management, and personalisation.

It is timely to consider the emphasis we place on particular capabilities in PhD training and academic development. And it is also important to ask how we might help the PhD to lean more into the future by making some fine-tuned adjustments to admissions, training, and the nature of the thesis.

At the University of South Australia, we have introduced the Project-based PhD as part of the Enterprise Hub initiative. It’s a slight adaptation to more traditional approaches, beginning with admissions. Rather than wait for individual students to come to our door—and treating them to the slowest admissions process for any kind of degree—we have switched to a recruitment model in which they apply to be a part of a project team, or to propose a project for a team. Training is being optimised to focus on the capabilities and futures orientation that great employees, founders, and academics need. Slight adjustments to the thesis model must be our next consideration, and specifically, providing all students with enhanced opportunities to disseminate and further build the impact of their work. How can dissertation format and mode step up to the challenge of broadened conceptions of the PhD?

The PhD is a 100-year start-up poised for the next transformation.

***

Marnie Hughes-Warrington is DVC, Research and Enterprise at the University of South Australia.

Pat Buckley is Dean of Graduate Studies at Uni SA.

Inger Mewburn is Director, Research Training at ANU’s College of Asa and the Pacific.

ANU’s PostAc University team have an app, to ” help PhD students into non-academic research careers”.