by JAMES GUTHRIE

In stark contrast to the University of Sydney’s annual report,[i] Macquarie University reveals a lack of cash and a firm reliance on debt. Given that the financial news is mixed, it highlights staff and students’ achievements. For similar reasons, perhaps, it places the university’s diverse stakeholders at its centre, identifying these as, amongst others, members of parliament, staff and students, alumni, and industry and community partners.

VC S. Bruce Dowton, sent an all staff email recently highlighting the financial circumstances of Macquarie University as outlined in the 2021 Annual Report.

He said, “The underlying financial trajectory for the university is heading in the right direction. In 2022 the university is focused on planning for growth in revenue through existing channels, improving the student experience, and embedding the cost savings achieved in 2020-2021.”

His 2021 key financial highlights were that operating income increased by 2.6 per cent to $1182m and that the reduction in international fees was only about $40m. Operating expenses decreased by 7 per cent to $1121m. This was achieved by reducing employee-related expenses by $72m.

Management seems to explain the net result improvements by a so-called one-off gain from the restructuring of Education Australia Limited, a company owned by 38 Australian universities that promote the Australian university sector and its internationalisation: “Net Result improved to a surplus of $62 M, including a $43 M one-off gain from the University’s shareholding in Education Australia Limited. Excluding one-off items, the Underlying Net Result was a surplus of $19 M.”

However, as indicated in the notes, the financial re-engineering of Education Australia Limited highlights this investment was not a one-off gain, as MU had booked income in previous years.

The Vice Chancellor then states, “I can report that the university’s cost base has been successfully reset to a more sustainable footing. This follows University-wide workplace change programs which are complete for academic staff, with the Professional Services Transformation in its final stages of implementation.”

In the previous analysis of the 2020 annual report[ii], we highlight several high costs at Macquarie University that appeared not to have been resolved from the previous period. First its failed public-private partnership (PPP). Macquarie University holds the asset, expenses and management of the only public university hospital not supported by government funds. MU borrowed and then subsidised the running of the hospital by not charging commercial rent or interest on about $300 million in loan funds from 2008 onward.

Macquarie University Hospital is Australia’s only university-owned teaching hospital, with both the parent and entities controlled by Macquarie University. The hospital is an on-going source of loss for the parent. The parent charges a “peppercorn” rent to the hospital and covers debt repayments. At a guess, the hospital accumulated losses may run over $100m since 2008. After some financial re-engineering in the last decade and impairment, the hospital is now valued at $99m.

Second, Macquarie University is involved in another PPP which is rarely debated publicly: a medical faculty and commercial venture for Indian students and the private Indian medical group, the Apollo Hospitals Group. Apollo is a big private healthcare group in India and that country’s first corporate hospital. The question here is, what does this PPP cost Macquarie University in operating expenses and is the medical faculty being subsidised by other faculties? This subsidy could have only come from student fees and government money for teaching.

Third, the costs associated with other PPPs include service concession assets of about $100m. There is little discussion about value for money in entering into these commercial arrangements for student accommodation and other buildings and properties.

Fourth, MU has significant debt.[iii] The reconciliation of liabilities arising from financing activities is $679m, with total borrowings of $645m. There are significant costs associated with borrowing; $24m for the year.

Fifth is the cost of remuneration for the vice chancellor and senior executives. In 2021 the VC earned over $1 million, and each executive group member over $450,000. The New South Wales premier’s salary is about $300,000.

Turning to other matters, the accounting for staff has reverted to only staff numbers reported to the government in March 2021. All fixed term and casual staff are accounted for as a so-called full-time equivalent.[iv] In the 150 pages of the Macquarie University annual report, the only numbers for staff are those in the following Table.

| Category | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Academic | 1799.7 | 1730.7 | 1551.5 |

| Professional | 2034.2 | 2006.4 | 1841.3 |

| Total | 3833.9 | 3737.1 | 3392.8 |

Note: Includes continuing, fixed-term and casual staff FTE as at 31 March (government submitted numbers).

We argue that the headcount, especially the actual number of people who lost employment at Macquarie University, would be in the thousands and not the 442.

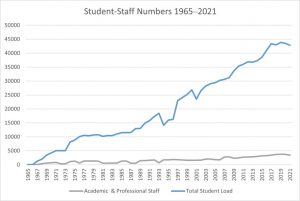

Figure 1 (click to expand) below highlights staff productivity compared to the total student load over more than five decades since Macquarie University was founded. The top line is the total student enrolments, and the second bottom line is staffing numbers. The number of casual staff stopped being disclosed in about 2010. Again, we see the human cost. The internationally accepted optimum teaching staff to student ratios are one to 20. A lower staff‒student ratio provides a much more excellent student experience and significantly better results. A lower ratio can help students cultivate closer relationships with their lecturers, have more rapid access to assignment feedback and engage in more interactive seminars and discussions.

In 2020 Macquarie University ranked 195 in the Times Higher Education rankings. The rankings include a teacher‒student ratio, which for Macquarie University was 1:65, the worst of any university in Australia. Many universities were in the 20‒30 range; the University of Sydney had a ratio of 1:19.

The staff‒student ratio can be calculated in various ways. It can be a straight headcount and classification into local and international onshore students, or students can be counted as equivalent full-time students (EFTSL). The same applies to counting university staff. Either a straight headcount and classification into academic and non-academic by full-time, part-time, or staff, including casual staff, can be counted as a so-called Full-Time Equivalent. Regardless of which counting method is used, the numbers tell us little. Teaching is a human activity that cannot be condensed into a statistical calculation. It involves actual staff and actual students working together.

Finally, the NSW Auditor General only conducts a financial statement audit and does not review the other information in the report, such as information on staffing, student numbers and senior executive salary. The Council of the university is responsible for this other information. The scope of the financial audit does not include or assure that a university has carried out its activities effectively, efficiently and economically. This is a matter of a performance audit. The New South Wales Auditor General has these powers, and we urge her to review all public universities operating in New South Wales to determine if they are administered effectively, efficiently, and economically.[v] Those findings would make interesting reading. Especially as the redundancies were based on a doomsday scenario that did not eventuate and the so called cost savings have been all about reducing employment and conditions of academics and professional staff.

Emeritus Professor James Guthrie AM, Professor of Accounting, Macquarie Business School

(i) Mattei, G., Grossi, G. and Guthrie, J. (2021), ‘Exploring past, present and future trends in public sector auditing research: A literature review’, Meditari Accountancy Journal, Vol. 29 No. 7, pp. 94-134.

(ii) NSW AG re performance audit of the NSW unis debt strategies. James Guthrie (2021), CMM https://campusmorningmail.com.au/news/nsw-unis-debt-strategies-have-they-forgotten-lehman-brothers/ here

(iii) Tom Smith and James Guthrie (2021), CMM https://campusmorningmail.com.au/news/universities-should-report-real-staff-numbers-not-accounting-abstractions/ here

(iv) James Guthrie (2022), CMM https://campusmorningmail.com.au/news/uni-sydneys-annual-report-reveals-a-big-bucket-of-money/ here

(v) Guthrie, J. (2021), ‘The charitable purpose of Macquarie University is to advance education’, Campus Morning Mail, https://campusmorningmail.com.au/news/the-charitable-purpose-of-macquarie-university-is-to-advance-education/ here