by Inga Davis

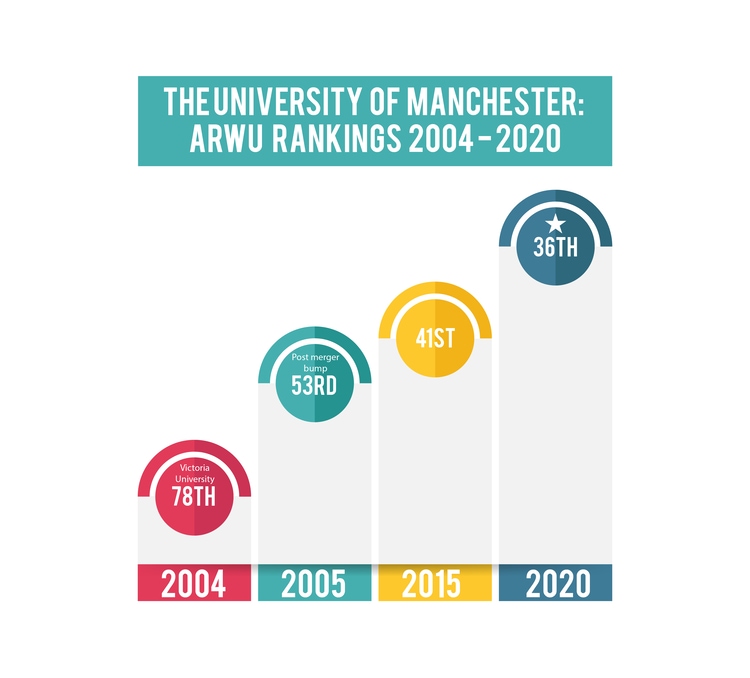

The Victoria University of Manchester (Victoria University) and the Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) merged to create the University of Manchester in 2004. Alan Ferns, Associate Vice-President External Relations and Reputation at Manchester, was Head of Public Relations at Victoria University. He played a key role at the helm of communications and branding strategy for the merger project which created The University of Manchester, today ranked 36th in the ARWU and 27th in the QS.

On the eve of Alan’s retirement from Manchester, I asked him about the critical ingredients of Manchester’s merger success.

The institutions that merged

There was the Victoria University of Manchester (Victoria University), which was the full civic university, with a medical school, arts, science, social sciences and humanities and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), which focused on engineering, science, and management.

Both institutions were old and established, UMIST being the older of the two. It was established in 1824 as a technical college born in the industrial revolution to provide skills and training for people to work in textiles and other industries. The Victoria University was set up as a non-religious college in 1851. It was the first of England’s big civic universities, after the ancient universities of Scotland and Durham and Oxford and Cambridge, when it became a university in the 1870s. In terms of history, size and subject mix, it had much in common with the universities of Melbourne and Sydney.

The Victoria University and UMIST existed as friendly rivals for most of their history and their campuses were physically close just south of the city centre.

Pre-merger collaborators

In a handful of areas. There was a joint department of materials, a joint accommodation service and a joint careers service.

There were quite a few duplicate departments – chemistry, mathematics, physics, engineering, and business schools.

With cultural differences

There was a difference because of the relative size of each institution. At the time of merger, Victoria University was about 20,000 students and UMIST had about 6,000. Victoria was a bit more “ivory tower” and “red brick”. UMIST was a bit more “down to earth”, they had many industrial partnerships and relationships and a collegiate culture. With only 6,000 students and a couple of thousand staff, people knew one another

How the merger came about

A joint committee had been established with representation from the two universities and an independent chair from industry. They were tasked with the exploration of future collaboration opportunities. We assumed the committee might consider closer collaboration in areas of overlap, or perhaps handing over some functions where we would be better doing things together. Initially, no one considered the committee would recommend merger, but it did – and that was a complete surprise. Following this, the universities agreed to publicly announce the establishment of a formal exploratory group. This was a very carefully planned announcement. I worked on it with my counterpart at UMIST as we had to make sure both campuses and the local community found out at the same time.

From here, we set up a formal structure including about eight project teams to look in detail at what might be the implications of a merger for research, the academic structure, the student experience, finance, brand, student recruitment and admissions. I was tasked with leading the communications and branding group, jointly with my counterpart at UMIST. Our task also involved the planning and executing communications and engagement during the merger discussions, scoping and planning the launch of the new brand and engaging with key external stakeholders.

Key considerations for research profiles

The scale and strength that could be achieved through a merger of research teams, infrastructure and faculty, particularly in expensive big science subjects, was certainly a key consideration for the merger and it emerged as an underpinning theme in the narrative for the new institution.

Strategically, we knew our combined research strength would begin to challenge the big universities in the golden triangle (Oxford, Cambridge, and London) for grants, funding and staff. At that time, there was no other university north of the golden triangle that could give them a run for their money.

Science research was becoming more expensive, so it was crazy to have two chemistry departments within a mile of each other competing with each other, rather than with other universities around the UK or the world.

Industrial issues in the restructure

One of the things we guaranteed early on, to give the merger the fairest chance of success, was that there would be no job losses by way of compulsory redundancies. That was important to get the two communities engaged and eventually supporting the merger. There was a rationalisation of jobs through voluntary severance some years after the merger. The whole merger process was aided by special funding grants from the local and national government.

A unique model of institutional leadership

I think it is important to note, that the Manchester merger was driven by ambition and not financial necessity. The two universities would have been moderately successful if they had continued as separate institutions. What was exciting was the sense that we could build something better on the platform of the two institutions together. The game changer in this regard was the arrival of the late Professor Alan Gilbert, from Australia as the inaugural vice-chancellor of the new university. What Alan Gilbert did was to articulate a global vision and ambition for the new university and convince our communities that this was achievable. He painted a picture that the combined institution could be so much more impactful than the sum of its parts. I think he was incredibly good at spotting the opportunities that others did not necessarily see. He was visionary and inspirational. I remember him saying we needed to forget about Oxford, Cambridge and London…. That we were playing on the world stage and if we don’t use that as our reference point we won’t be setting up the right dynamic. He also introduced world rankings into the vision – he wanted us to be top 25 in the world.

Separately, another of the key ingredients for success was that both of the vice chancellors of Victoria and UMIST were coming to an end of their terms, and both retiring. Also, both chairs of the governing bodies agreed that they would step down and there would be a new chair appointed to lead a new governing body for the new university. Those were important considerations. Effectively what happened was that we had three vice chancellors, the VCs of Victoria and UMIST led their respective institutions to the point of merger, and Professor Gilbert was appointed and shaped the strategy and structure of the newly formed university.

Getting the name right

We deliberately waited to address the name of the new institution as people were obsessing over it. What we did say to staff was that we would let them decide what the name would be, once other key decisions about the merger were made, so that it was an issue we took off the table until then. Staff ultimately voted for “The University of Manchester” but there were six options in contention. We were very clear that the new institution would be entirely rebranded.

Making the merger happen

The governing bodies of both universities met simultaneously, and both took the independent decision to disestablish their universities and to create a brand-new institution. From that point it was about 18 months planning for the launch of the new institution. That is where the work was done in earnest as to what the governance and structure would be. There was a huge amount of work in this period and essentially a team of people dedicated to setting up the new university was formed, while the two institutions continued under the leadership of their respective vice chancellors

From the outset, it was agreed this would be a merger of equal partners. In every decision taken, one university did not dominate the other. Negotiations were a genuine partnership, committees had equal representation. When we invented new structures and process, they were not based on the existing structures of either institution. Every new department and school had a competitive process to recruit leadership.

A new Royal Charter was developed to form The University of Manchester and the Queen formally launched the University in 2004 with Professor Alan Gilbert as President and Vice Chancellor. We unveiled a new brand and logo for the new university, with signage on campus all changed over the weekend, ahead of the launch. When people arrived at work on the Monday, it was a new look university.

Rankings impact

Initially, rankings did not feature strongly on our agenda. This is because at that time they were not the driver for universities that they are today. The Research Excellence Framework had been introduced in the UK, and we knew that we were likely to score more highly if we merged. Having said this, the merger has in fact had a pronounced impact on the ranking of the University of Manchester. Some subjects where departments were combined – like chemistry, physics, life sciences and business and management – have done exceptionally well since the merger.

Alan Gilbert was critical in shifting our gaze to the world stage. He recruited two Nobel laureates to join the new university and we had two more of our own academics who won the Nobel Prize in subsequent years. This had a profound impact on the University’s standing and ranking.

We have seen a lot of movement in the global rankings driven by an uplift in our research and publication metrics and an actual improvement in our research performance and in our global reputation. Of course, we received an early boost in the Shanghai Jiao Tong (now ARWU) from the merger itself and then from our Nobel Prize winners. Today we are 27th in the world on the QS, 36th in the ARWU and top 5 in the UK.

In addition, social responsibility and impact have been key goals and a feature of the university since its foundation in 2004, so we were particularly delighted earlier this year when we emerged in first place internationally in the Times Higher Education (THE) Impact Rankings.

The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) Rankings 2004-2020. In 2004 Victoria University was ranked 78th in the ARWU. Post-merger with UMIST the ranking rose to 53rd (in 2005). Attributed in large part to the positioning strategy commenced by Professor Alan Gilbert, The University of Manchester ranked 36th in the ARWU in 2020.

The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) Rankings 2004-2020. In 2004 Victoria University was ranked 78th in the ARWU. Post-merger with UMIST the ranking rose to 53rd (in 2005). Attributed in large part to the positioning strategy commenced by Professor Alan Gilbert, The University of Manchester ranked 36th in the ARWU in 2020.